In 1972 Jack Trout and Al Ries wrote three seminal articles on brand positioning that were published in Advertising Age. Thirty-six years later the merits of their thinking holds steadfast. This is an excerpt of their article The Brand Positioning Era Cometh.

Remember The Mind Is A Memory Bank

To better understand what an advertiser is up against, it may be helpful to take a closer look at the objective of all advertising programs – the human mind.

Like a memory bank, the mind has a slot or “position” for each bit of information it has chosen to retain. In operation, the mind is a lot like a computer.

But there is one important difference. A computer has to accept what is put into it. The mind does not. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

The mind, as a defense mechanism against the volume of today’s communications, screens and rejects much of the information offered it. In general, the mind accepts only that new information which matches its prior knowledge or experience. It filters out everything else.

For example, when a viewer sees a television commercial that says, “NCR means computers,” he doesn’t accept it. IBM means computers. NCR means National Cash Register.

The computer “position” in the minds of most people is filled by a company called the International Business Machines Corp. For a competitive computer manufacturer to obtain a favorable position in the prospect’s mind, he must somehow relate his company to IBM’s position.

Yet, too many companies embark on marketing and advertising programs as if the competitor’s position did not exist. They advertise their products in a vacuum and are disappointed when their messages fail to get through.

Seven Brands Are The Mind’s Limit

The mind, as a container for ideas, is totally unsuited to the job at hand.

There are more than 500,000 trademarks registered with the U.S. Patent Office. In addition, untold thousands of unregistered trademarks are in use throughout the country.

During the course of a single year, the average mind is exposed to more than half a million advertising messages.

The target of all this communications ammunition has a reading vocabulary of no more than 25,000 to 50,000 words, and a speaking vocabulary of one-fifth as much.

Another limitation: The average human mind, according to Harvard psychologist George A. Miller, cannot deal with more than seven units at a time. (The eighth company in a given field is out of luck.)

Ask someone to name all the brands he or she remembers in a given product category. Rarely will anyone name more than seven. And that’s for a high-interest category. For low-interest products, the average consumer can usually name no more than one or two brands.

Yet in category after category, the number of individual brands multiply like rabbits. In 1964, there were seven soft drinks advertised on network television. Today there are 22.

To cope with complexity, people have learned to reduce everything to its utmost simplicity.

When asked to describe an offspring’s intellectual progress, a person doesn’t usually quote vocabulary statistics, reading comprehension, mathematical ability, etc. “He’s in seventh grade” is a typical reply.

This “ranking” of people, objects and brands is not only a convenient method of organizing things, but also an absolute necessity if a person is to keep from being overwhelmed by the complexities of life.

You see ranking concepts at work among movies, restaurants, business and military organizations. (Some day someone might even come up with a rating system for politicians.)

Mind Puts Products On Ladders

To cope with advertising’s complexity, people have learned to rank products and brands in the mind. Perhaps this can best be visualized by imagining a series of ladders in the mind. On each step is a brand name. And each different ladder represents a different product category.

Some ladders have many steps. (Seven is many.) Others have few, if any.

For an advertiser to increase his brand preference, he must move up the ladder. This can be difficult if the brands above have a strong foothold and no leverage or positioning strategy is applied against them.

For an advertiser to introduce a new product category, he must carry in a new ladder. This, too, is difficult, especially if the new category is not positioned against an old one. The mind has no room for the new and different unless it’s related to the old.

That’s why if you have a truly new product, it’s often better to tell the prospect what the product is not, rather than what it is.

The first automobile, for example, was called a “horseless” carriage, a name which allowed the public to position the concept against the existing mode of transportation.

Words like “offtrack” betting, “leadfree” gasoline and “tubeless” tire are all examples of how new concepts can best be positioned against the old.

Names that do not contain an element of positioning usually die out. The “Astrojet” name dreamed up by the American Airlines is an example of a glamorous, but unsuccessful name, because it lacks a positioning idea.

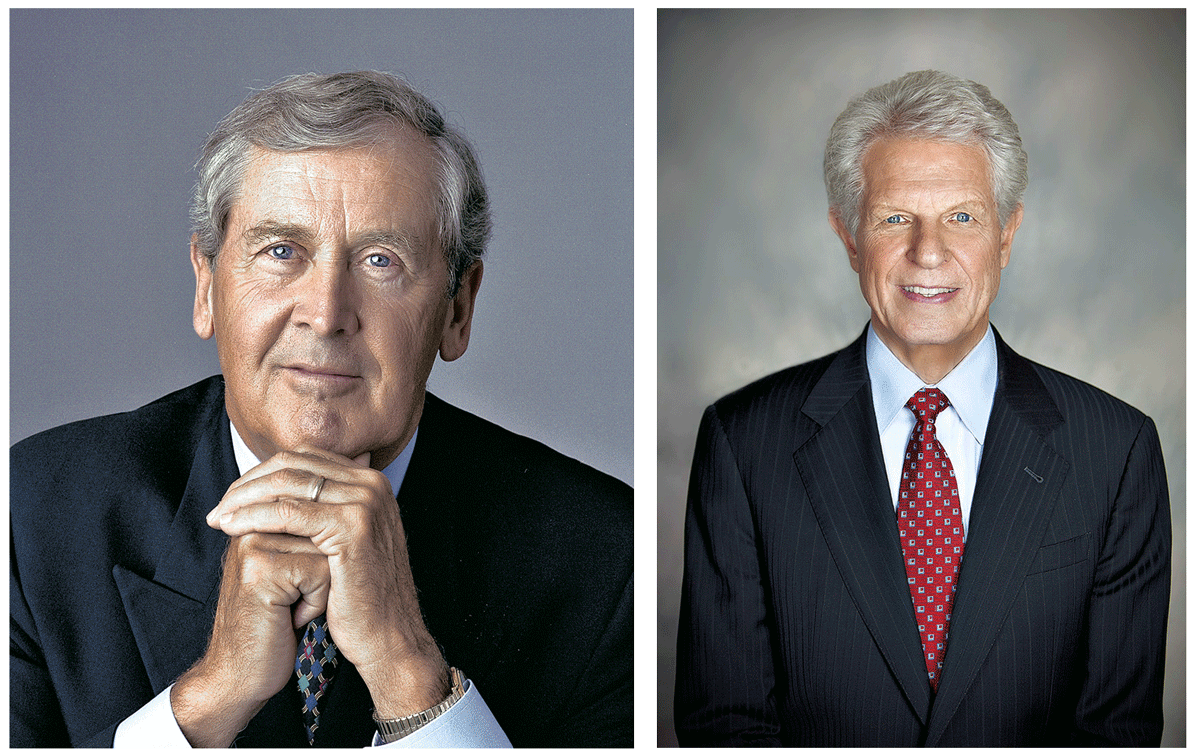

Trout & Ries, Circa 1972

The Blake Project Can Help: The Brand Positioning Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education