Companies cannot be good at everything. They face trade-offs in their business. For example, they trade off performance attributes and the costs of providing products or services. More legroom means higher willingness-to-pay but fewer passengers per plane and higher costs per passenger.

Similarly, there is a trade-off between the cost of providing goods and services and how inconvenient it is for a customer to access them. As passengers, we would love to have a car waiting for us at every corner of town—it would translate into convenient access. But it also would mean lower vehicle utilization and higher costs.

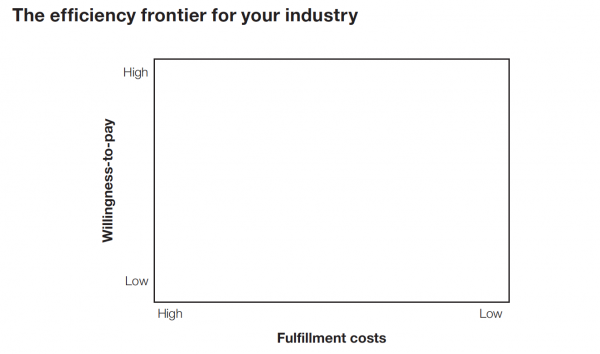

Such trade-offs can be illustrated graphically in your industry using the efficiency frontier framework below.

This will help you draw the efficiency frontier in your industry through the following steps:

1. Pick your most relevant competitors.

2. Rank them in order of the willingness-to-pay that their products or services create. In other words, put yourself in the shoes of a typical customer and ask yourself which product or service is the most desirable, ignoring the price you would have to pay for it. For example, if someone else paid for it (though you would still have to do the purchasing, transaction processing, and waiting), would you rather receive a Mercedes C-class, a BMW 328, a Tesla Model 3, or a Lexus IS? Ask yourself how well your competitors perform along the dimensions of performance and fit attributes, location, timeliness, and cost of ownership.

3. Rank your competitors and yourself in terms of fulfillment costs. Ask yourself, what is the average cost per transaction that you have versus your competitors? Note that this is the average cost. For instance, one firm might spend a lot on advertising, but if it has many customers, it can spread this cost over many transactions, affecting its average cost per transaction only by a little. A simple rank ordering is sufficient.

4. With this information, you can position yourself and your competitors. Next, draw the line that represents the efficiency frontier. This is the group of firms that are farthest up and to the right on the plot—that is, the firms that have the highest willingness-to-pay for any given level of fulfillment costs (or, conversely, that have the lowest cost for any given level of willingness-to-pay).

Once you have filled out the efficiency frontier framework, you can think about the following questions:

- Where are you relative to the efficiency frontier? Are you on the efficiency frontier, or are there firms providing a similar (or even higher) willingness-to- pay while enjoying lower fulfillment costs? Keep in mind that not every firm in an industry is likely to be on the frontier.

- If you are not on the efficiency frontier, what efficiency improvements do you plan to pursue in order to reduce your fulfillment costs?

- Assuming you are on the efficiency frontier, do you feel that you are in the right spot on the frontier? Or do you feel that you should rethink the trade-off between willingness-to-pay and costs (e.g., sacrifice some efficiency to provide a better product or service)?

- What are the trends in your industry? Is there a pressure to lower costs (moving to the right), or do you see your firm win over its rivals by providing products and services with a higher willingness-to-pay (moving up)?

- Are there new technologies that have allowed some of the firms already in the industry or potentially new entrants to push out the frontier? Do you see new business models breaking the trade-off between willingness-to-pay and fulfillment costs?

The Competition Between Power Tools And Neckties

It’s easy to ask, “What are your most relevant competitors?” But that seemingly simple question is much more complicated than one might initially suspect. Consider the following example, inspired by a remark on substitutes by Michael E. Porter, one of the most influential scholars of modern business strategy.

Imagine you work for a power-tool company. As a power-tool company, who are you competing against? One way of answering this question is by looking at who else is producing power tools. Framed this way, competitors such as DeWalt, Bosch, Ryobi, Hilti, and similar tool makers might make it onto your list.

Another way of tackling this question is to reframe it and ask, “For what purpose do customers use power tools such as a circular saw?” Chances are your customers might want to use the saw to cut some wood, maybe in order to build a new dining table.

When asked this way, the question reveals that you, as the maker of circular saws, are not just competing with other power-tool makers, you also are in competition with the makers of dining tables. The more customers are willing to tackle the job of building dining tables themselves, the more money they will pay to power-tool companies versus furniture stores.

But we can reframe the question again and ask, “Why do people buy power tools in the first place?” When you ask the question this way, you will quickly realize that one of the most common reasons for power-tool purchases is that customers are shopping for Father’s Day or Christmas presents. You probably sense where we are going with this argument. In this framing of the question, you realize that power-tool makers are competing with other providers of Father’s Day or Christmas gifts, neckties being one of the most important ones.

So, when we ask you to think of your competitors, how broadly should you look? We propose that you start with those companies that you are directly competing against—in our example, this would be the other makers of power tools. But, especially when it comes to imagining innovation and disruption, we want you to think about the competition more broadly by considering the ultimate needs that your customers want to fulfill. Disruption typically happens from players outside your current market. Just remember: hotels were disrupted not by other hotels but by Airbnb . . .

Contributed to Branding Strategy Insider by: Nicolaj Siggelkow and Christian Terweisch. Excerpted from Connected Strategy: Building Continuous Customer Relationships For Competitive Advantage, (Harvard Business Review Press, May 21, 2019] Copyright 2019 by Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

The Blake Project Can Help You Grow: The Brand Growth Strategy Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Growth and Brand Education