Peter Drucker, the father of modern management once wrote that, the purpose of a business is to generate new customers, and only two functions do that, marketing and innovation. All other business functions are expenses. That piece of advice has since been ignored by many business leaders with but a few exceptions.

Today, when top management is surveyed, their priorities in order are: Finance, sales, production, management, legal and people. Missing from the list: marketing and innovation. When one considers the trouble that many of our business icons have run into in recent years, it is not easy to surmise that Drucker’s advice would have perhaps helped the management to avoid the problems they face today.

Ironically, David Packard of Hewlett-Packard fame once observed that “Marketing is too important to be left to the marketing people.” But as the years rolled on, rather than learn about marketing and innovation, executives started to search for role models instead of marketing models.

Tom Peters probably gave this trend a giant boost with the very successful book he co-authored, In Search of Excellence. Excellence, as defined in that book, didn’t equal longevity, however; many of the role models offered there have since foundered. In retrospect, a better title for the book might have been In Search of Strategy.

A very popular method-by-example book has been Built to Last by James Collins and Jerry Porras. In it, they write glowingly about “Big Hairy Audacious Goals” that turned the likes of Boeing, Wal-Mart, General Electric, IBM and others into the successful giants they have become.

The companies that the authors of Built to Last suggest for emulation were founded from 1812 (Citicorp) to 1945 (Wal-Mart). These firms didn’t have to deal with the intense competition in today’s global economy. While there is much you can learn from their success, they had the luxury of growing up when business life was a lot simpler. As a result, these role models are not very useful for companies today.

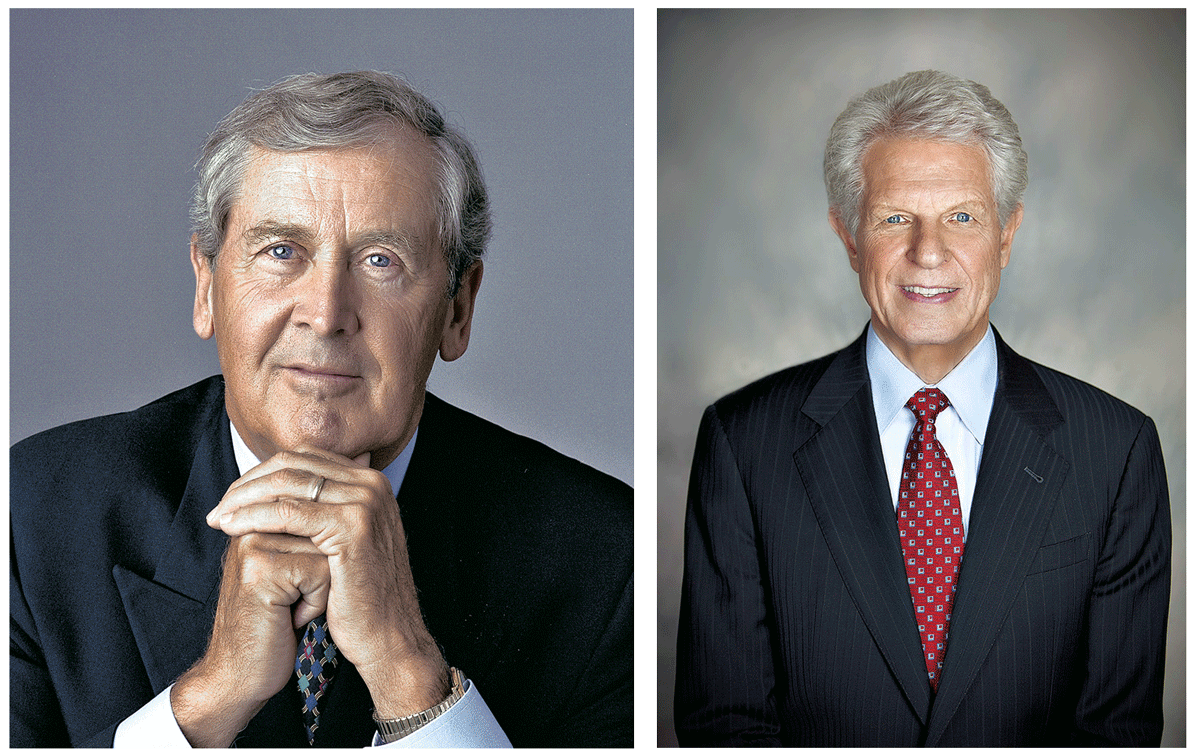

Nothing brings this to light more than when you study what I call, the tale of two companies. It’s the story of General Electric versus United Technologies. One has had terrible marketing. The other has had good marketing.

An article in the New York Times (November 12, 2009) titled “As G.E. Struggles, A Rival Steps Up” should be compulsory reading for all management people everywhere. It’s the story of two companies that are sprawling industrial corporations with concentrated portfolios in aerospace, power and infrastructure. It’s the story of United Technologies versus General Electric. It’s also a case study in marketing the right way and the wrong way. It’s about what should be done to run a multiple business company. And what shouldn’t be done. Let’s start with the “shouldn’t.”

General Electric invented electricity which is certainly a nice start. It was created out of a combination of 8 firms controlling 90 percent of the market. (Those were the good old monopoly days.) With that kind of start it’s no wonder that they fell in love with their name and their logo. As the years rolled on we saw a massive amount of line extension. GE became what people call a megabrand. It was General Electric everything whether it was light bulbs, jet engines, nuclear power plants, locomotives, medical devices or even money as they bet big on finance via General Electric Credit. And, as you know, that bet hasn’t worked out very well.

What’s a General Electric? It’s a messy unfocused conglomerate.

If you’ve read any of my many books or that of my former partner Al Ries, you’ve noticed that we have always been voices crying in the wilderness about the perils of line-extension. Why? Because the arrival of a specialist in a category will do enormous damage to a fuzzy, line-extended brand. My books have endless examples so let’s not go there.

United Technologies is the exact opposite of General Electric. They have assembled a powerful portfolio of well positioned specialist brands that are powerhouses in their respective categories. You have Carrier, the inventor of air conditioning. You have Sikorsky, the inventor of helicopters. You have Pratt and Whitney jet engines, Norden electronics and Otis, the king of elevators. And rather than bet on things like mortgages and leasing, they stayed close to their manufacturing knitting.

What’s a United Technologies? It’s an industrial Procter & Gamble with big, powerful brands.

How is one doing versus the other? Well, as the NY Times reported, the numbers are there to look at. Last year, United Technologies returned 10 times GE’s total shareholder return. Go back a decade and investors who rolled their dividends back into United Technologies stock have had a 185 percent return while GE’s shareholder are down 55 percent. General Electric is not a pretty story.

Today, there is a growing legion of competitors coming at them from every corner of the globe. Technologies are ever changing. The pace of change is faster. It is increasingly difficult for CEOs to digest the flood of information out there and make the right choices.

So what is a CEO to do?

The trick to surviving out there is not to stare at the balance sheet but simply to know where you must go to find success in a market. That’s because no one can follow you (the board, your managers, your employees) if you don’t know where you’re headed.

How do you find the proper direction? To become a great strategist, you have to put your mind in the mud of the marketplace. You have to find your inspiration down at the front, in the ebb and flow of the great marketing battles taking place in the mind of the prospect. Here is a four-step process to pursue:

Step 1: Make Sense In The Context

Arguments are never made in a vacuum. There are always surrounding competitors trying to make arguments of their own. Your message has to make sense in the context of the category. It has to start with what the marketplace has heard and registered from your competition.

What you really want to get is a quick snapshot of the perceptions that exist in the mind, not deep thoughts.

What you’re after are the perceptual strengths and weaknesses of you and your competitors as they exist in the minds of the target group of customers.

Step 2: Find The Differentiating Idea

To be different is to be not the same. To be unique is to be one of its kind.

So you’re looking for something that separates you from your competitors. The secret to this is understanding that your differentness does not have to be product related.

Consider a horse. Yes, horses are quickly differentiated by their type. There are racehorses, jumpers, ranch horses, wild horses, and on and on. But, in racehorses you can differentiate them by breeding, by performance, by stable, by trainer, and on and on.

Step 3: Have The Credentials.

There are many ways to set your company or product apart. Let’s just say the trick is to find that difference and then use it to set up a benefit for your customer.

If you have a product difference, then you should be able to demonstrate that difference. The demonstration, in turn, becomes your credentials. If you have a leak-proof valve, then you should be able to have a direct comparison with valves that can leak.

Claims of difference without proof are really just claims. For example, a “wide-track” Pontiac must be wider than other cars. British Air as the “world’s favorite airline” should fly more people than any other airline. Mercedes should have superb engineering.

You can’t differentiate with smoke and mirrors. Consumers are skeptical. They’re thinking, “Oh yeah, Mr. Advertiser? Prove it!” You must be able to support your argument.

It’s not exactly like being in a court of law. It’s more like being in the court of public opinion.

Step 4: Communicate Your Difference

Just as you can’t keep your light under a basket, you can’t keep your difference under wraps.

If you build a differentiated product, the world will not automatically beat a path to your door. Better products don’t win. Better perceptions tend to be the winners. Truth will not win out unless it has some help along the way.

Every aspect of your communications should reflect your difference. Your advertising. Your brochures. Your Web site. Your sales presentations.

There’s a lot of hogwash in corporate America about employee motivation. Brought to you by the “peak performance” crowd, along with their expensive pep rallies. The folks who report to you don’t need mystical answers on “How do I unlock my true potential?” The question they need answered is, “What makes this company different?”

All this leads to the final question, “So how do you avoid losing focus and undermining your brand?”

The answer is simple: Sacrifice. Giving up something can be good for your business. When you study categories over a long period of time, you can see that adding more can weaken growth, not help it. The more you add, the more you risk undermining your basic differentiating idea. Sacrifice comes in three forms.

- Product sacrifice is staying focused on one kind or category of product. Duracell in alkaline batteries, KFC in chicken. Southwest Airlines in short-haul air travel. It’s the opposite of trying to be everything for everybody.

- Attribute sacrifice is staying focused on one kind of product attribute. Nordstrom on service. Dell on selling direct, Papa John’s Pizza on better ingredients. Your product might offer more than one attribute, but your message should be focused on the one you want to preempt. It’s keeping a narrow focus on your story.

- Target market sacrifice is staying focused on one target segment in a category which enables you to become the preferred product in that segment. DeWalt for professional tools, Pepsi for the younger generation, Corvette for the generation that wants to be young. If you chase another segment, chances are you’ll chase away your original customers.

So there it is in simple terms. Branding is putting a brand in the consumer’s mind along with its point of difference. The trick is to stay focused on what the brand stands for and not get greedy with it. It’s apparent that the Jack Welch General Electric was driven by greed or their desire to dazzle Wall Street with their financial performance. United Technologies was focused on marketing their powerful brands.

And the best marketing seems to have won.

The Blake Project Can Help: The Brand Positioning Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education