The first year of study for a PhD in Marketing is a confusing affair. I vividly remember long days spent at Lancaster trying to decode the journals of marketing with the creeping sensation that I may have bitten off more than I could chew. The first theoretical model I fully understood was the Hierarchy of Effects.

It was a simple model that had been around since the 30s, but long before I got to grips with the Elaboration Likelihood Model or Existential Phenomenology (don’t ask), it provided my first moment of academic clarity.

More than a decade since the completion of my PhD most of the arcane theories that underpinned my thesis have faded from memory. The Hierarchy of Effects, however, stays with me – partly because it was my first, but also because it is still the most useful.

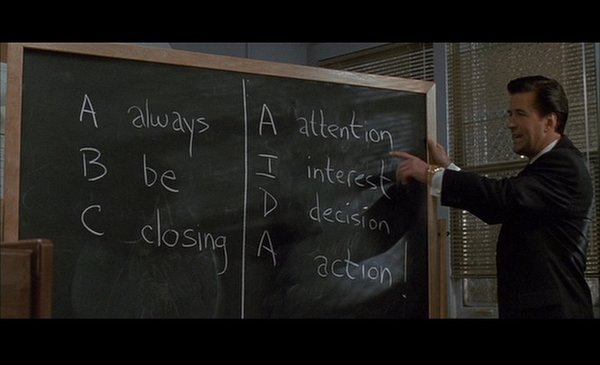

Many marketers know the Hierarchy of Effects, but usually by a different name. Some call it AIDA, others the demand chain, still more the purchase funnel. Whatever the name, it invariably begins with the total potential market for your brand. This pool of potential customers then progress through a series of stages that can include awareness, preference, purchase and, hopefully, loyalty.

It’s a hierarchy because we lose people as they move through the sequence.

And it’s a hierarchy of effects because at each stage marketers must achieve different communication goals. They might be encouraging trial, rewarding loyalty, or communicating brand associations, depending on the stage the target customer has reached.

It is impossible to specify what the stages and goals will be in your hierarchy because every brand is different. Consequently, every brand manager must do the research to identify the steps that link mass ignorance to total loyalty and use them to drive their marketing.

It is only when the hierarchy is identified that it reveals its power.

Marketers who take the trouble and the 5% of the budget needed to build one are in an inestimably superior position to those who soldier on regardless. With a hierarchy, a marketer can measure the number of consumers who occupy the different stages in their funnel. With these measurements in place they can set goals. Not crappy, pointless goals like ‘build brand affinity’, but real ones such as ‘increase purchase intention from 17% to 40% in the target segment within three months’.

These goals ensure that marketers can better brief and select their communication agencies. They also enable marketers to go back and re-measure their hierarchy after the pre-specified period to see if they have achieved their goals.

They can report these results to senior management and use them to calculate the performance-related pay of their agency partners.

A hierarchy also enables integrated marketing communication. Without one, integrated marketing usually means making your different communications speak with the ‘same voice’ – whatever that means. With a hierarchy in place, marketing can be truly integrated: different tools doing different things at different times to drive different customers through the funnel.

Look hard enough and you will find that behind every great marketing execution there is invariably a hierarchy. Explore the way in which P&G is able to ensure all its agencies are measured and motivated by their performance.

Take a look at almost every single McKinsey marketing engagement for a major client.

Call it whatever you want, but if you haven’t got one, you really can’t call yourself a marketer.

30 SECONDS ON … THE HIERARCHY OF EFFECTS

– The origins of the Hierarchy of Effects can be traced back to 1898 and American salesman St Elmo Lewis. He believed that rather than simply closing a sale, a proficient salesperson must ensure Attention, maintain Interest, create Desire and finally get Action.

– In 1961 researchers Robert Lavidge and Gary Steiner published a seminal paper in the Journal of Marketing that outlined the Hierarchy of Effects and recommendations on advertising measurement. They also noted that consumers appeared to progress through cognitive (thinking), then affective (feeling) and finally conative (intention) stages.

– Also in 1961, Russell Coney outlined his hierarchy-based planning model, known as DAGMAR: Defining Advertising Goals for Measured Advertising Results. Coney’s model formed the precursor for the account planning age and for the scientific revolution that was about to take place in the advertising industry.

This thought piece is featured courtesy of Marketing Week, the United Kingdom’s leading marketing publication.

The Blake Project Can Help You Grow: The Brand Growth Strategy Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Growth and Brand Education